At the Blue Hill Weather Observatory and Science Center, the highest point in Greater Boston, Don McCasland pointed to a long white board on the ground used to measure snow accumulation throughout the season. McCasland said this winter, there isn't much to measure.

“I've been working here for 22 years and, um, this is tough,” said McCasland, an atmospheric educator and program director at the observatory. “We've had some winters where we've had to walk through mud to get to certain [areas]but nothing to the extreme we have had this winter.'

While many locals are relieved they haven't had to fire up their snow blowers all winter, climate scientists see a symbol of a rapidly warming New England.

According researchers, the southern part of the northeastern US — which includes Boston — could see almost total snow loss and frigid temperatures by the end of the century, especially in coastal areas. That means this year's warm winter could be the new norm.

So far, this is the fifth warmest recorded winter for Boston — with average temperatures at 36.7 degrees — compared to normal average winter temperatures of below freezing. This year, Worcester recorded its warmest winter on record with average temperatures of 33.7 degrees, compared to its usual average of 27.4 degrees.

But McCasland said what's remarkable about this winter isn't the lack of snow or warmer temperatures — it's the near-complete lack of snow accumulation.

“If we get three inches of snow and it's 30 degrees, that snow is going to compact very quickly,” he said. “And then if it's 40 degrees the next day, it's gone — out of sight, out of mind.”

The lack of snow cover is a problem for flora and fauna that have adapted to freezing winters for millennia. Take trees for example, which may have sensitive root systems close to the ground. Without snow cover, roots can be damaged by freezing and thawing, which would be less likely with an “insulating blanket of snow,” said Andy Finton, a tree ecologist at the Nature Conservancy.

“I think a winter without snow is not going to destroy entire populations of plants or animals,” he said. “But it's one more stressor that can reduce the abundance of a population, whether it's a tree species or a small mammal or a bird species.

At Mass Audubon's Drumlin Farm Wildlife Sanctuary in Lincoln, biologist Tia Pinney points out a number of small mammals that neither migrate nor hibernate—like voles and moles and field mice—but instead find protection under the snow, both from predators and from the cold.

Although there was some white stuff on the ground, Pinney said it wasn't enough to create a habitat for critters that dwell under the snow. To demonstrate, she picked up a handful from the ground, crushing the icy-white mixture in her bare hands.

“I can feel many different layers of ice and snow where it's frozen and thawed and refrozen and thawed again,” he said, adding that ice doesn't provide the same level of protection for organisms living beneath it.

New England winters are warming faster than any other season — and it's happening faster here than in most of the country, said Elizabeth Burakowski, a climate change researcher at the University of New Hampshire. Burakowski grew up in southern New Hampshire in the 1980s and said the winters she knew as a child are gone.

“Winters have been snowier in the past, winters have been colder in the past,” he said. “When I look at the climate data from stations all over the northeastern United States, we see that winter has actually lost its cold, it's lost its snow.”

Burakowski said the length of the cold spell — from the first freeze to the last — is about three weeks shorter than it was a century ago. This trend has accelerated in recent years.

None of this means we won't see proper snowstorms in the future, Burakowski said, but Boston winters are likely to be more like winters in more southern regions.

“What we grew up with is now changing to a climate that's a lot more like, say, northern New Jersey,” he said with a laugh. “And I don't know about you, but I'm not one to plan winter vacations in northern New Jersey.”

By the end of the century, our winters could resemble the winters we see today in Virginia or North Carolina, Burakowski added. We would probably need to go farther into northern New England to have the same winters that Boston had just decades ago.

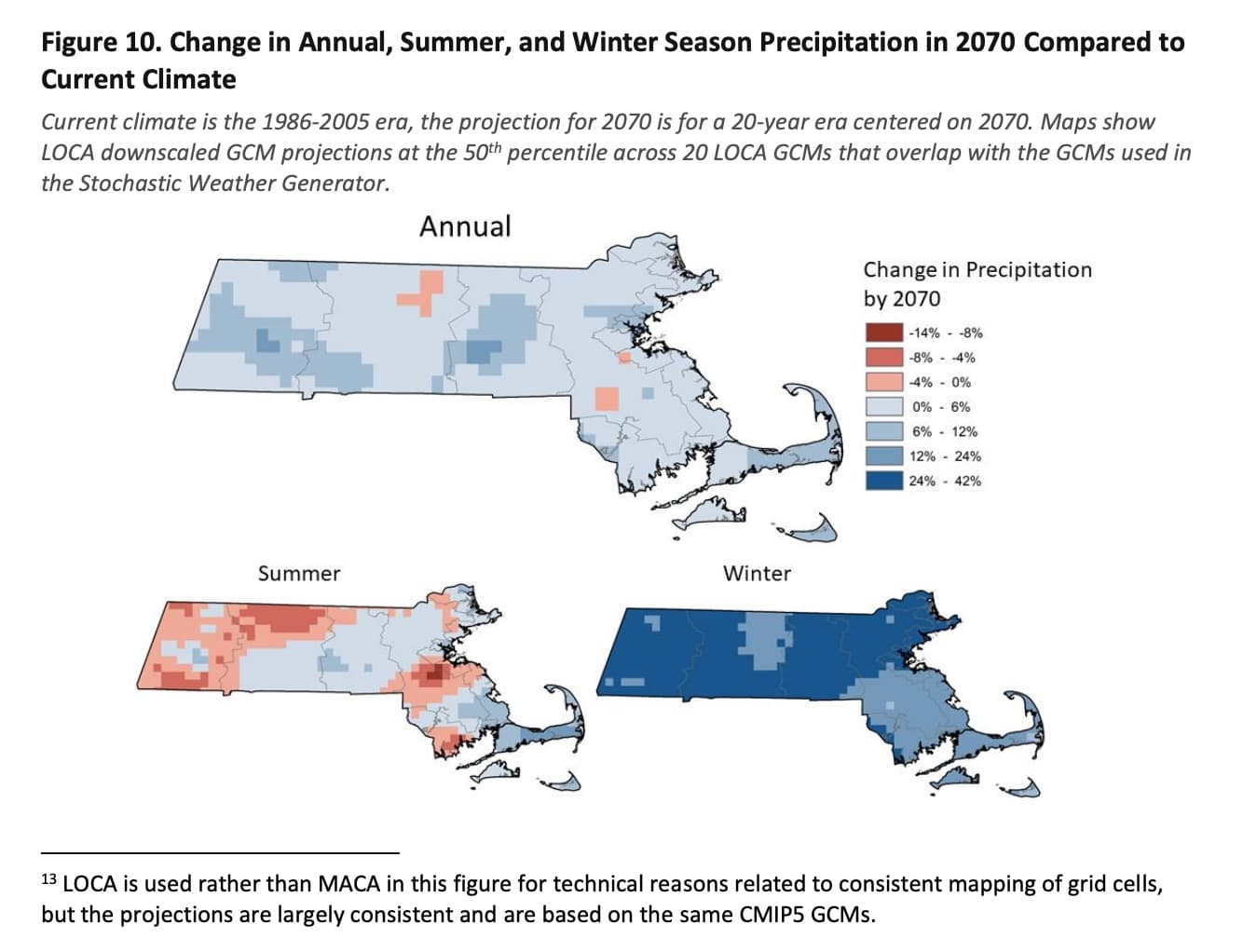

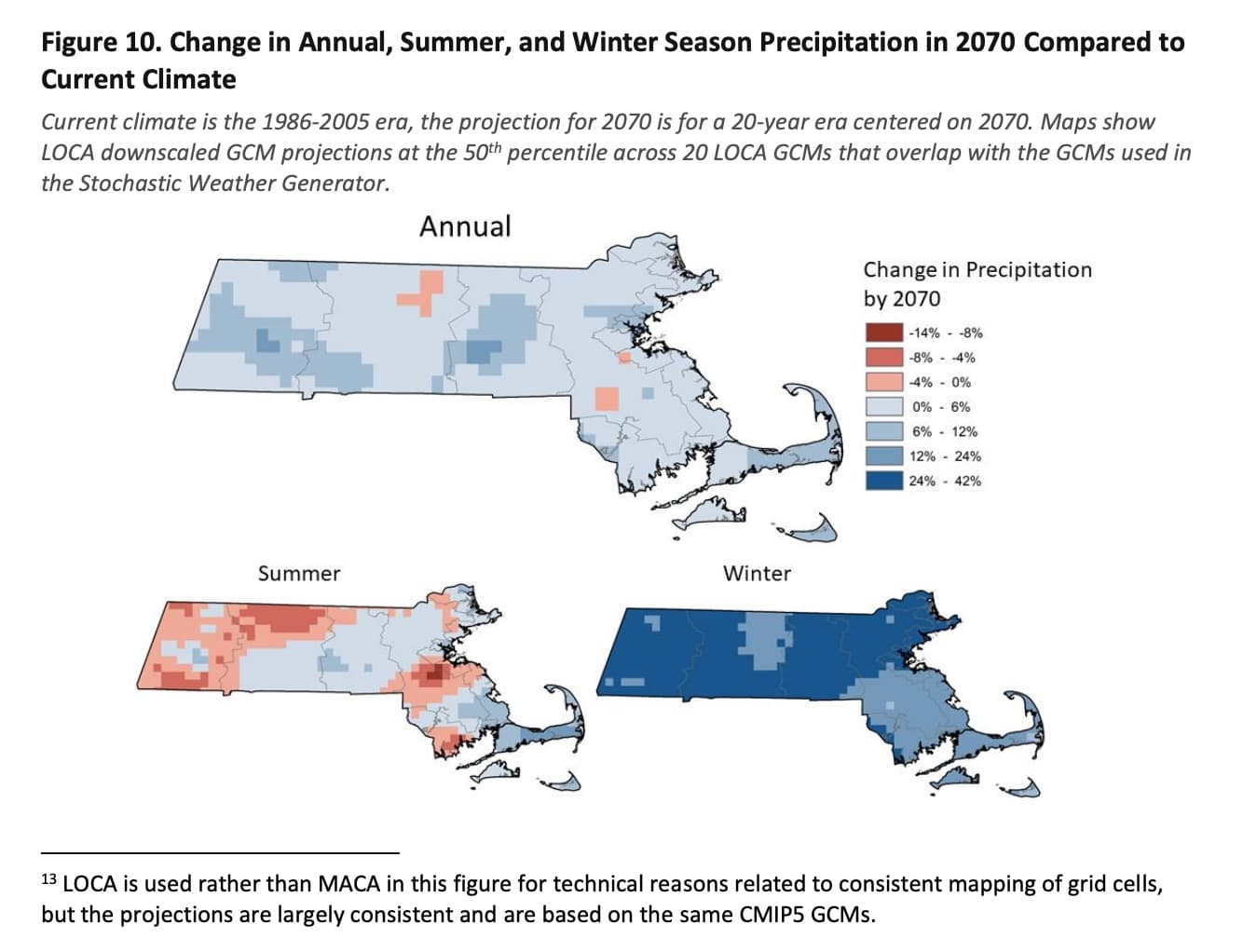

The cold months are also sure to bring fewer winter wonderlands and more sloppy slush landscapes in the coming years, he said Emma Gildesgame, who studies climate change adaptation at the Nature Conservancy. He pointed to the climate models they predict significant increases in winter precipitation levels in the coming years.

More precipitation, combined with warmer winters, means we're likely to see mud on the ground during the winter, Gildesgame said. “It's dangerous and we should add more salt.”

And what will these snowy, wet winters mean for our sense of self as hearty northerners? Gildesgame thinks we should recalibrate.

“As New Englanders we go sledding, have snow days, shovel our spots and fight over a parking spot,” he said. that changes.”

Cutting emissions could help slow climate change, experts say, but even with drastic interventions, New England winters will continue to warm.

There is, perhaps, a silver lining to this unusual winter, say the scientists interviewed for this story: it's a wake-up call. And it's a reminder to enjoy our fleeting snowstorms, even if we have to get the shovels out again.