Posted on

Nearly 50 years later, the famous photo is a 'teaching tool', not just an 'artifact of America's past'

Photographer Stanley Forman and victim Ted Landsmark, a distinguished professor at Northeastern, reflect on the 1977 Pulitzer Prize-winning photo, “The Soiling of Old Glory.” Even today, Landsmark says, it can be used to spark debate about race.

You probably know the picture.

For millions of people, the image of a white teenager using an American flag to attack a black man in Boston's City Hall Square on April 5, 1976, epitomized the hatred surrounding the Boston bus crisis and the tenuous state of modern race relations. in the United States.

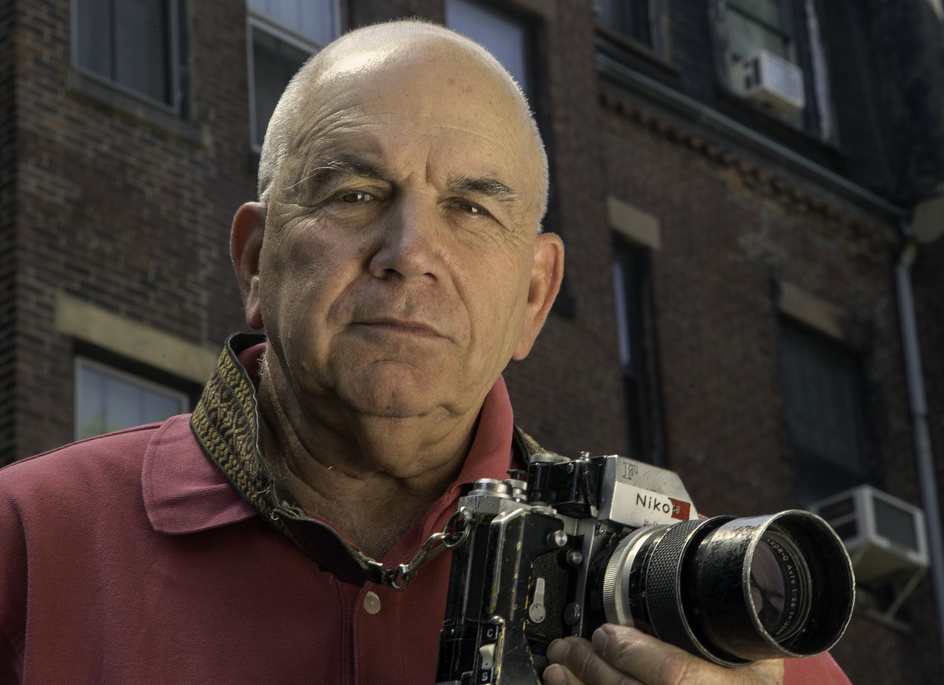

But photographer Stanley Forman didn't realize he had captured something iconic until hours after the event.

“To me it was just another racially charged demonstration,” says Forman. “I know it sounds silly, but it was a few hours later when I realized the significance of the image. … I just knew it was an anti-bus protest that went down the drain.”

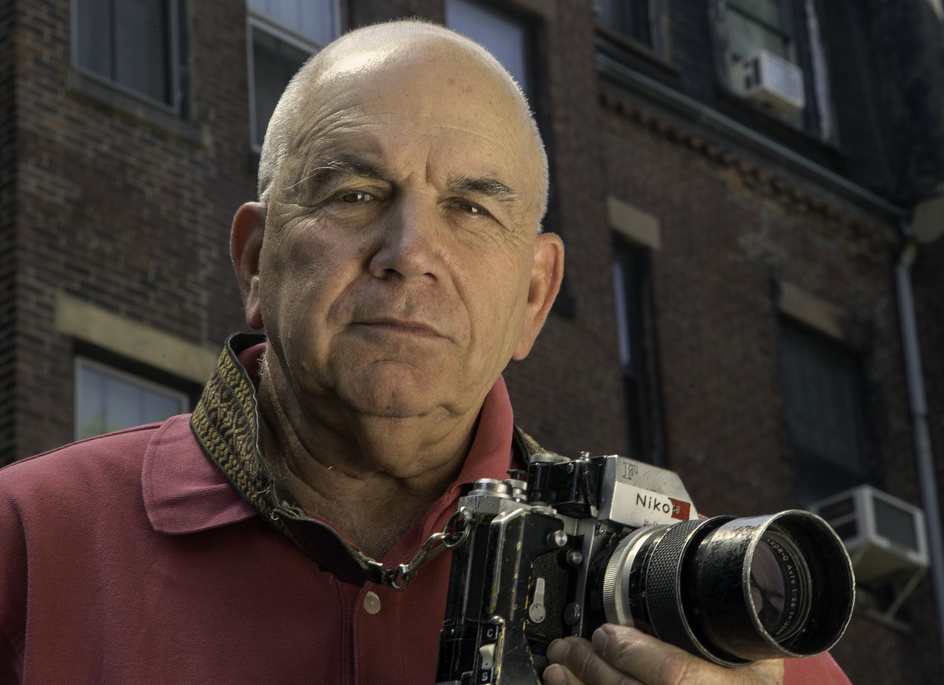

Ted Landsmark, the victim of the attack, meanwhile, didn't immediately realize he had even taken a picture.

“It wasn't until after the event that I realized there were media,” says Landsmark, distinguished professor of public policy and urban affairs and director of the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University.

Joseph Rakes, the striker 47 years ago, did not respond to a request for an interview.

The photo, called “The Soiling of Old Glory”, appeared in the US newspaper Boston Herald the next day, was distributed around the world and won the Pulitzer Prize for Spot Photography in 1977.

This image is a reminder of the work that needs to be done now to address issues of racial injustice, discrimination and inequality, some of which are worse today than they were then.

Ted Landsmark, distinguished professor of public policy and civic affairs at Northeastern;

It has since served as a reminder of the city and country's racist past and as a prophetic symbol for the present, often reappearing in public when issues arise regarding the American flag and racial protest. In fact, Landsmark and Forman are scheduled to be on CBS Sunday Morning on June 18 to talk about the photo.

As for that moment in 1976, Landsmark was heading to Boston City Hall to meet with the city planning agency to advocate for increased training and job opportunities for local residents and people of color on neighborhood public works projects.

He had been involved in the social justice movement since before high school and visited Selma, Alabama and Atlanta as a college student. He also followed civil rights and antiwar protests while studying law at Yale University, where he was the political editor of the Yale Daily News.

But he had “no idea” that an anti-bus protest would take place almost at the same time as his meeting. He didn't even see the protesters until they both approached a corner from the opposite direction.

“I quickly realized that if I kept walking straight, they were going to turn the corner and go wherever they were going — which turned out to be the federal courthouse — and I could just keep going to my meeting,” Landsmark says.

Meanwhile, Foreman saw that the protesters were on the march to intercept Landsmark and had his camera ready.

“I'm excited about breaking news, so I like to think that I have common sense and anticipation, and when I look around, I try to take a picture of what I'm doing,” Forman says.

The attack was not immediate.

“What the photo shows is that a significant number of youths had actually already passed me as at that point the flag bearer and others who attacked me circled back to attack me from behind,” says Landsmark.

But the attack was dramatic. A protester hit Landsmark from behind, breaking his nose. Rakes, the standard bearer, waved the flag at Landsmark and missed his face by inches. In total, the attack lasted less than 10 seconds.

Foreman was shooting away.

“You go there, you look around, you adjust the size of the scene and I put myself in a position where I'm going to get the best picture or a good picture – I always want to get the best picture – or where I'm going to get a good picture and it's going to be better,” says Forman.

He took a photo that was the best.

He also angered the protesters and had to be escorted back to his car by Boston's deputy police chief.

“I was very scared that day and for many days afterward,” Forman says. “I was like, 'There it is.'”

Landsmark, meanwhile, had also attracted attention. there were media waiting for him as he left the hospital.

But his involvement in civil rights and social justice had prepared him.

“I had thought about what I might say if I was ever in a difficult civil rights situation and asked to respond in that moment,” Landsmark says. “I had been harassed in the past by people who opposed civil rights, had participated in mass arrests during anti-war protests, had known activists who had been beaten and/or killed because of their commitment to achieving social justice, and I KNEW that a time in my life when I would be called upon to make thoughtful comments as an activist and advocate for racial justice.”

Nearly 50 years later, he continues to advocate.

“The thing is, there's a tendency to see the photo as evidence of how patriotic symbols can be used for divisive purposes throughout American history,” Landsmark says. “I also think this image is a reminder of the work that needs to be done now to address issues of racial injustice, discrimination and inequality, some of which are worse today than they were then: residential segregation, school segregation, lack of access to affordable housing, are all issues that are statistically more heinous and complex today than they were then, despite the progress that has been made in reaching people around voting rights or public accommodations.”

In fact, Landsmark keeps a copy of the photo in his office at Northeastern, using it as a “teaching tool” when asked about it.

“While the photograph stands for a moment on its own, it is also a starting point for deep conversations about how we as ethical people can best share the resources we can develop through our talents, connections and hard work” , says Landsmark. “It's a teaching tool that is a progressive platform for moral and racial and social justice discussions rather than an artifact of Boston's and America's past.”

Forman, meanwhile, is looking at the picture – which would be the second of three Pulitzers. he also won in 1976 for a sequence of a woman and child falling from a collapsing fire, and he shared an award with the Herald American staff in 1979 for their coverage of the 1978 Blizzard—and he sees pure hate. In fact, he sees the image as one of a series of photos he took that day.

“When I look at the faces and the rage, and if you look at all the photos, how some of the people in the picture went from point a to point b. It was so hate-filled,” Forman says. “Everyone is calling it a racist image, it's a hateful image – the whole range of hate.”

And as Landsmark continues to support, Forman continues to take pictures.

“Scanners are my music,” Forman says during the interview, as police scanners screech in the background. “I hope I can chase news until I can't.”

“I'm still looking for the next great picture,” continues Forman. “I think there's another banger out there for me.”

And if another such situation arises, Landsmark urges the next generation to be prepared.

“You never know when a moment will come when you have to say and do the right thing to promote a sense of justice,” says Landsmark. “Well, that means you have to be ready all the time.”

Cyrus Moulton is a reporter for Northeastern Global News. Email him at c.moulton@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @MoultonCyrus.