Khadija Arian still remembers everything that happened before and after August 15, 2021, the day the Taliban took over Afghanistan. He heard gunfire in the streets of the capital, Kabul, the night before. “I felt like bullets were going through my heart because I knew the Taliban were close,” he says.

Arian received a panicked call days later saying she had to get out of Afghanistan now. People were running for their lives and she had to get out. Her favorite meal that her mother prepared for dinner—beef and onion noodles known as mantu—would become lunch.

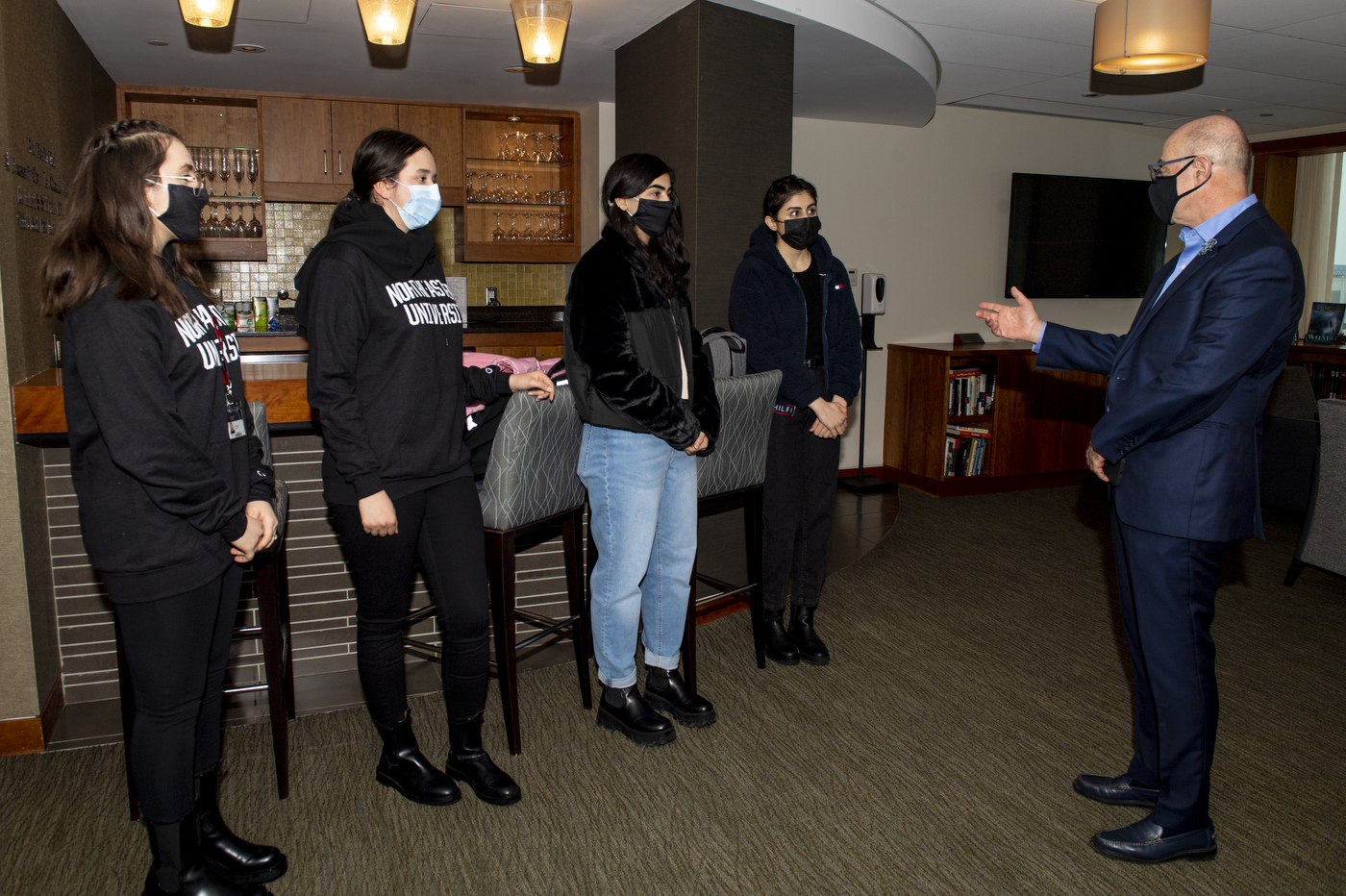

Arian, along with Sara Sherindil, Lala Osmani and Mashal Aziz, are newly arrived Afghan refugees on Northeastern's Boston campus this semester. They first met as finance and accounting students at American University in Afghanistanthe country's first private university.

Lala Osmani, a junior business major, received a call from her mother telling her the Taliban were on the move. “You have to go home now,” she remembers her mother saying. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University.

It was created in 2006 with funding from the US government. Former US first lady Laura Bush visited in 2005 in the area where the university would eventually be located.

There were only 50 students and very few women when it first opened. Later, more women like Arian, Sherindil, Osmani and Aziz would arrive.

But then August 15th came. Their country was once again under Taliban rule, and with it the women's dreams of a higher education dashed. The four feared that the conservative political and religious group would bar women from pursuing their degrees, as they did to an earlier generation of women in the 1990s, when they last controlled Afghanistan.

“They wouldn't let us continue our education,” says Sherindil.

In total, more than 76,000 refugees arrived in the US as part of it Business Allies Welcome, which marked the end of the 20-year military campaign. The greater air transport of people ever commissioned by the US Air Force.

On a frigid January day, four of these refugees sit in the Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex on Northeastern's Boston campus wearing Northeastern-branded heavy coats and face masks. Just a few days ago, they were living in a US camp in New Jersey with thousands of other refugees.

They identified some of their compatriots in the camp as the lucky ones inside the infamous US cargo plane with desperate civilians clinging to the outside of the aircraft. The image seen around the world became synonymous with the hasty military exit of the United States.

“When we got to New Jersey, we met a lot of people who entered America on that plane,” says Sherindil.

Over the course of nearly an hour, the students describe in fluent English those last turbulent moments in Afghanistan before leaving for a country he had never been to before.

Mashal Aziz is a senior pursuing a degree in finance and accounting. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University.

Arian—the one who looked forward to her mother's dumplings—is from Kabul. She was on her way to renew her Afghan passport with her uncle when she received a call that the city was under siege.

“Suddenly we saw a rush of people on the streets. Everyone looked so confused, no one knew where they were going. It was like a scene from a movie,” he says. “You could see the fear on everyone's faces.”

“I even remember one guy trying to sell his car in the middle of this rush because he was so desperate. He said “Whoever wants this car can have it because I'm leaving.”

She later received an urgent message from American University telling her to pack up, await further instructions and begin saying goodbye to her parents and younger brother.

“The goodbye was so rushed,” she recalls. “Even today, I feel like I haven't said a proper goodbye to my parents.”

Osmani, a business administration major in her junior year, was at home in the city of Farah. It is one of the largest cities in western Afghanistan and is located near the border with Iran.

She was on her way to the bank to pay her university fees when she got a call from her mother telling her the Taliban were on the move. “You have to go home now,” she remembers her mother saying. People poured into the streets by the hundreds.

Her family didn't make the trip with her to the airport to say goodbye because “they didn't want to risk getting to the airport entrance and not getting in,” Osmani says. “There might be a problem if your name wasn't on the list.”

Sara Sherindil is from Kandahar, Afghanistan's second largest city. This is followed by a degree in Finance and Accounting. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University.

Meanwhile, Aziz, who lives in the densely populated Kapisa province, was also home when the Taliban took over the country. Her 12-year-old sister arrived from school to say her classmates were terrified, but before Aziz could recall the story, her voice trailed off and she burst into tears.

The four would eventually arrive at Kabul's main airport, where they described scenes of revelry. After the Taliban checked their names off a list, they left their hometown for neighboring Qatar before arriving months later in New Jersey.

Nostalgia quickly set in. They only had each other. All of them wondered when, how or even if they would be able to complete their studies.

There they met a representative of an organization based in New York, the New University in Exile Consortium. It places Afghan scholars, students and artists at participating universities and colleges. Northeastern is a member.

Khadija Arian remembers hearing gunshots the night before the Taliban took control. “I felt like bullets were going through my heart because I knew the Taliban were close.” Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University.

Northeast leaders discussed the opportunity to support refugees and quickly came to the same conclusion—”We are a global university and have a social responsibility to support these Afghan students who are looking for hope and education,” says Mallik Sundaram, associate vice president of international of enrollment management, and its dean Global Services Office.

“These students have already been through a lot. Northeastern will now be their home away from home and we are their family.”

Various offices sprung into action to manage the visa process, register students for courses and find housing just weeks before the start of the semester. The students were in the camp cafeteria when they opened an email from Northeastern notifying them that they had been accepted on a full scholarship, including housing.

“We were so happy, we just wanted to shout,” says Aziz. “I told them 'OK, girls, we're really at Northeastern.' When they arrived, they were quickly given designer gear. “We have a northeast hat, mask, hood, water bottle, everything,” laughs Sherindil.

With spring semester in full swing, they haven't had a chance to visit every corner of campus yet, but they're committed to exploring soon. Students also appreciate Northeastern's international mindset, which they believe helps others understand the ordeal they've just been through the past five months.

“I've gotten a lot stronger, so much more capable,” Arians says. “I will meet even more challenges and I will be ready for them.”

For media inquiriescontact media@northeastern.edu.