A purported “banned book list” from the state of Florida that includes classics like Harper Lee's “To Kill a Mockingbird” recently began circulating online. The list has since been judged a fake onebut not before causing massive outrage online.

For many people, it was another chapter in a story that has become all too familiar in recent years as book bans have increased in school districts across the country, according to a report from PEN America.

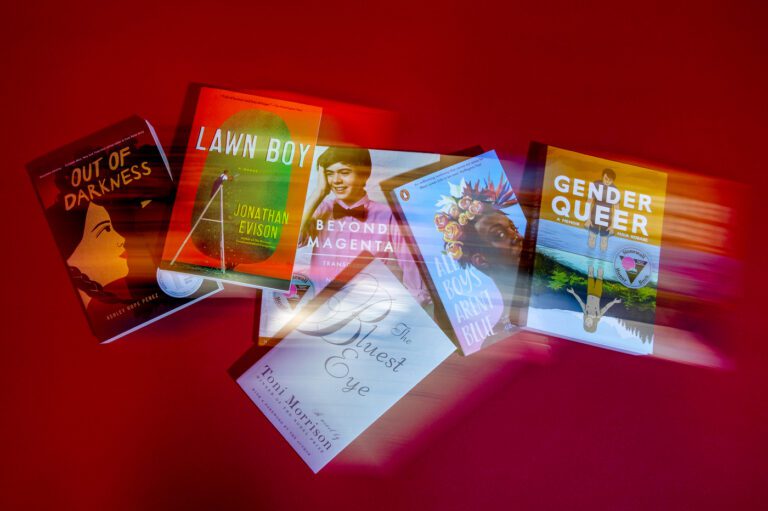

The free speech advocacy group found that from July 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022, 1,586 books were banned from classrooms across the country. The full list of bans includes cases from 86 school districts in 26 states that affected more than 2 million students in 2,899 schools.

*Information attributed to PEN America

“It breaks my heart,” says Jaci Urbani, associate professor and director of the early childhood special education program for Mills College at Northeastern in Oakland, California. “To say that would be a time in my life where there was this mass of banned books – we're going in the wrong direction.”

There were 713 book bans in Texas alone, and Pennsylvania had 456 bans, largely from a single mass ban.

And while Florida's “banned book list” was fake, book bans are far from rare in the state. According to the report, there were 204 book bans in nine months in Florida alone. In fact, Palm Beach County, Florida removed “To Kill a Mockingbird” from its school libraries earlier this year, only to return the book after reviewing the book's content.

For Urbani, recent book bans are troubling, particularly because they target works by or about people of color, LGBTQ people, and members of other marginalized groups. By further limiting who gets to tell the story in schools, Urbani says, US schools are failing not only students but also teachers.

“The books are a way for those of us who are uncomfortable with some of these conversations to start these conversations in classrooms,” says Urbani, who has been a classroom teacher in Philadelphia for 12 years. “There are so many wonderful, complex conversations we can have with these books.”

Book bans are far from a new phenomenon. Whenever there's a “culture war,” book bans tend to happen, he says Jonathan Friedman, director of free expression and education programs at PEN America and author of the report. However, the spate of book bans over the past year represents something other than the typically isolated cases of outraged parents.

“We're talking about developing a concerted effort to encourage people to bring the same kinds of challenges against the same books on the same grounds that are spread across multiple states and school districts,” Friedman says. “What's also really surprising is that it's been quite successful.”

Unlike in the past, the recent spate of book bans is not driven solely by concerned parents. Politicians have now become the main drivers of banning books in their states, Friedman says.

In October 2021, Rep. Matt Krause, a Republican Texas lawmaker, sent list of 850 books to school superintendents in districts across the state. He asked for a detailed record of whether their schools had copies of these books and, if so, where they were kept and how much money had been spent to acquire them.

According to Friedman, the work that went into compiling the list amounted to a “witch hunt.”

“It appears that he or someone on his staff did keyword searches in a library database, like 'LGBTQ' or 'racism,' and that's how they got on the list,” Friedman says.

Of the bans included in the report, 41 percent, or 644 bans, were initiated by state officials or elected leaders.

While the book bans are troubling, Urbani says they are symptomatic of a larger problem in the US public education system.

“We're not talking about race. We don't talk about injustices in school and really in society,” says Urbani. “Over the past few decades we've focused so much on standardized testing and not really focused on teaching kids how to think critically.”

When Urbani saw a mob storm the US Capitol on January 6, she saw it play out in real time.

“If there's any reason to say we should put more money into education, the evidence is there because there was so much overwhelming evidence that this election was not lost,” says Urbani. “People need to be able to take the evidence that's out there and think about it for themselves, and that's not what we've done in education.”

However, just because there are more book bans, doesn't mean they have the power to stay. In cases where large numbers of books were banned, the bans were often reversed, as in the case of the Central York School District in Pennsylvania.

In the wake of the George Floyd protests, Central York banned 441 books that were included in a list of optional resources for teachers who wanted to start conversations about race with their students. The list included a whole series of color character books and children's biographies about Rosa Parks and the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

Finally, the students organized a successful attempt to overturn the ban, but the case is indicative of how “phony” such large-scale bans often are, Friedman says.

However, in some cases, school districts go beyond simply banning books.

In May, Rapid City Area Schools in Rapid City, South Dakota, banned five books that had been selected for a 12th-grade English class by teachers but were deemed by administrators to contain “inappropriate, explicit sexual content.” About 350 new copies of those five books, which included the landmark LGBTQ graphic novel “Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic” and the dystopian novel “The Circle,” ended up sitting in a warehouse.

In May, the school district went one step further. Hidden in Rapid City Board of Education meeting minutes reports were made to investigate the contents of the books to see if they should be destroyed.

“As we are 25 minutes from Mount Rushmore, these four heads carved in stone would weep knowing that books were not only being pulled from the shelves—depriving young adults—but being destroyed,” Dave Eggers, author of “The Circle” , said a crowd gathered outside Mitzi's Books in Rapid City during a May event held in response to the ban.

“You don't want to hang out with booksellers,” he added.

For media inquiriesPlease get in touch media@northeastern.edu.