Many states in the Northeast have ambitious clean energy goals to help fight climate change. In the coming decades, they plan to add much more renewable energy sources like wind and solar to the grid, and use electricity instead of fossil fuels to power vehicles and heat buildings.

But right now, the power transmission system — the web of large power lines that carry high-voltage electricity over long distances — isn't robust enough to make those plans a reality.

Most existing transmission lines are at capacity and in many places, building renewable energy will require many new transmission lines to large population centers. In addition, some parts of the Northeast grids are not fully interconnected, making energy sharing difficult.

“It is widely understood that we will need more transmission to help all of our states meet our clean energy goals,” said Caitlin Peale Sloan, vice president of the Conservation Law Foundation in Massachusetts. “But it's very difficult to do.”

Energy infrastructure is difficult to install in the busy northeast and expensive to build, he said. So, to ensure that the region moves forward in a smart and cost-effective way, the six New England states, along with New York and New Jersey, look to the federal government.

Last month, they sent a letter to the Department of Energy, asking it to fund and coordinate an interregional transportation planning collaboration. The effort will bring together the states, regional network operators and, possibly, representatives from Canada. On June 28, the federal government he answered to say that he is interested in proceeding.

There are still many details to figure out, but in general, this unprecedented collaboration will assess onshore and offshore transmission needs and help find ways to improve the flow of power between the New England grid and grids in New York and New Jersey. The aim is to increase electrical reliability, make the grid more flexible and reduce electricity costs.

“We could do this individually as states, or possibly through our respective grid operators,” said Jason Marshall, Massachusetts' deputy secretary for federal and state energy affairs. “But there is a great advantage to having federal leadership involved in the process.”

In particular, the federal government employs many technical experts and has allocated millions of dollars to regional transmission planning.

“We're fortunate to have partners in the US Department of Energy and the Biden administration who are really focused on upgrading the grid and supporting clean energy,” Marshall said. “We are trying to take them up on their invitation and work very closely together to explore potentially different options for cross-regional projects.”

While it is useful to picture the transmission system across the country as a web of power lines, it is not an entirely accurate metaphor. It is more of a jumble of separate tissues. New England has its own web, New York has web, and New Jersey is part of a larger mid-Atlantic web. There are some relationships between them, but not enough.

New England, for example, can currently share about 1,700 megawatts of power with New York, Marshall said. But the federal study plan released earlier this year, which modeled potential clean energy and electrification growth, found that the regions likely need to be able to trade between 3,400 and 6,300 megawatts. New England and New Jersey do not currently have direct relations.

More connectivity means greater electrical reliability and cheaper power. To illustrate why, imagine that an offshore wind farm connected to Massachusetts unexpectedly shuts down on a day when electricity demand is high. Maybe New York or New Jersey have excess solar power that they can sell to New England to meet the need. That keeps the lights on and could prevent New England's grid operator from sending in a more expensive coal- or oil-fired power plant.

“You're building the capacity for more of that [renewable] the power to flow over our borders and displace more expensive fuels or fuel-based energy,” Marshall said. He added that a number of studies have found that interregional transmission planning has benefits such as “increased reliability and operational flexibility and lower energy prices.”

The Texas grid, which is not connected to outside areas, famously failed in the winter of 2021 during a prolonged cold snap. Electricity costs increased and there were massive blackouts. Over 200 people passed away, many from hypothermia. If Texas had been able to import power, the outages may have been less severe.

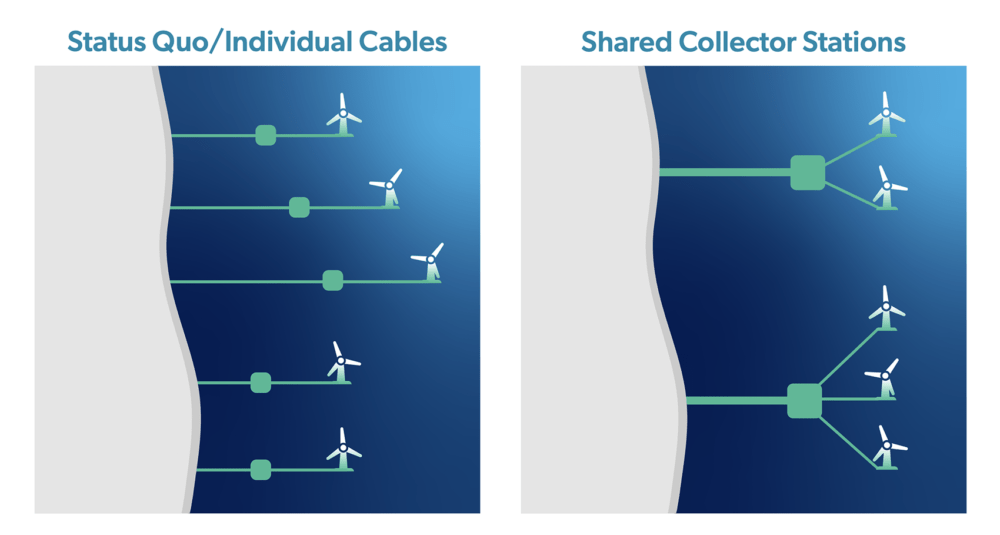

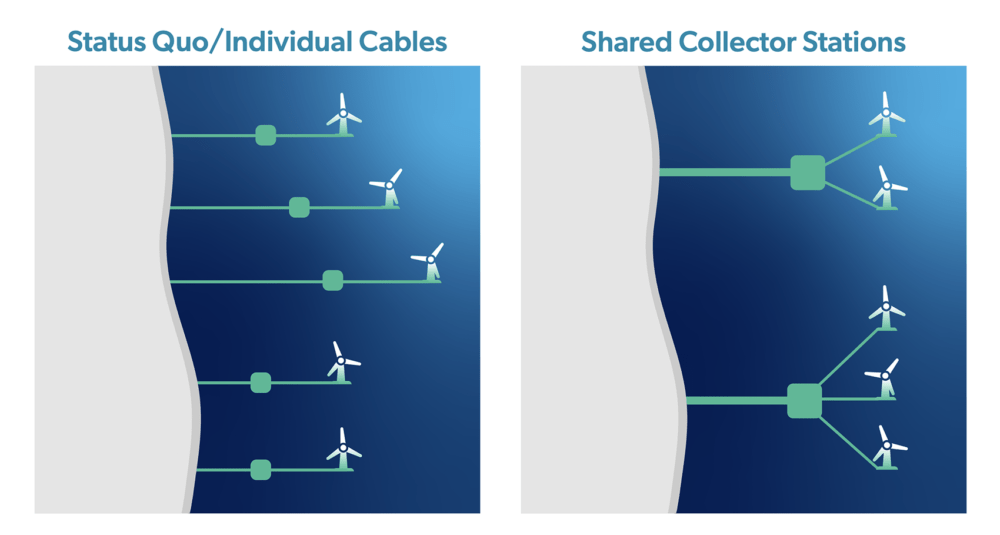

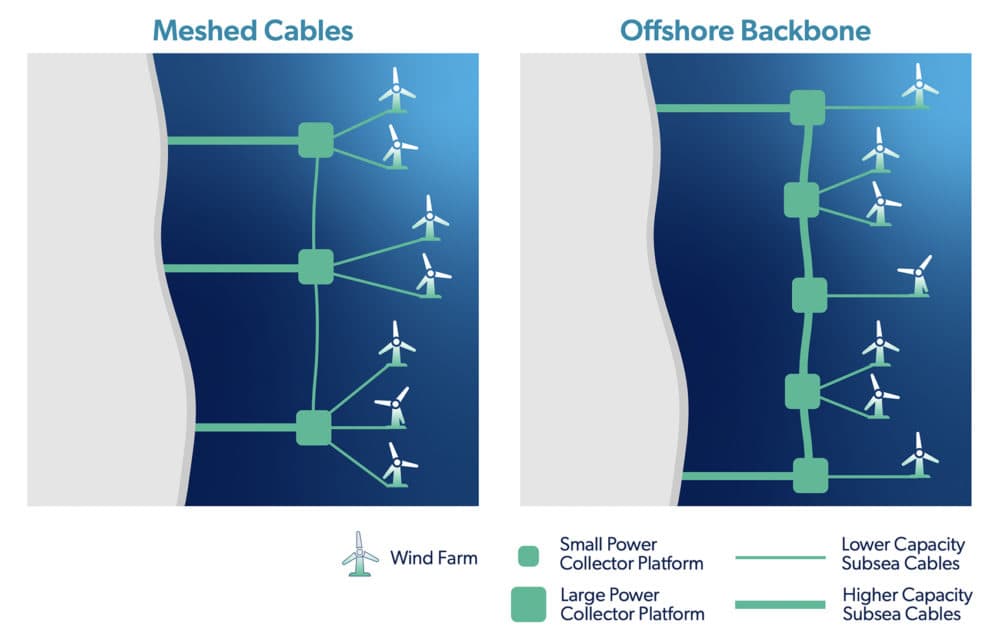

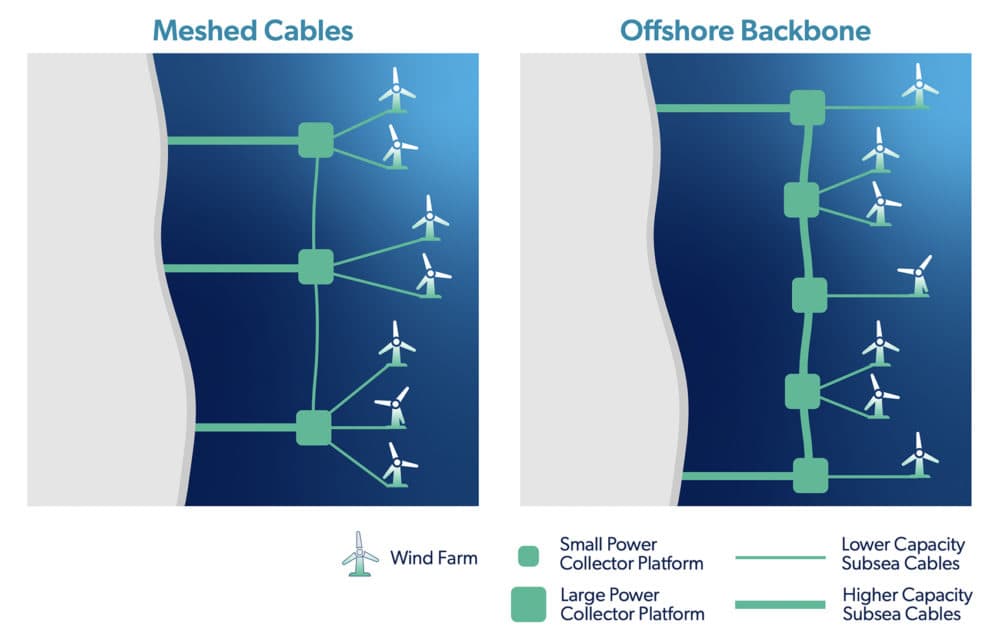

Having more cross-regional connections is not only important when things go wrong. It can also mean fewer power cords, in general. Consider the case of offshore wind: Right now, offshore wind developers plan to connect each individual wind farm to the onshore grid with its own undersea power line. As WBUR has previously reported, this system isn't ideal.

The alternative, a planned marine grid, would result in fewer ocean power transmission lines and require less work to upgrade the land-based transmission system. It would also be much less expensive.

The transmission partnership is an example of how Gov. Healey's administration is “pursuing innovative new approaches to accelerate our transition to clean energy,” Rebecca Tepper, the state's secretary of energy and environmental affairs, said in a statement . Massachusetts' climate plan calls for net zero emissions by mid-century, which will require a significant increase in renewable energy.

“We are grateful to our neighboring states and territories for coming together to propose this idea,” Tepper added.

The request from the eight states comes as Congress and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission are considering whether to establish “minimum transmission requirements” between network areas. The Ministry of Energy also takes over for two years study offshore transmission capabilities in the Atlantic Ocean.

Marshall, a state energy official, called the request from states “supplemental” to those efforts.

“We're trying to pull every lever we can to explore options to create a cleaner grid,” he said. “If we see all these potential benefits from interregional planning, why don't we try to do something proactively?”