A lack of top-quality schools in some Boston neighborhoods has undermined the city's bold efforts to provide access to good schools close to home, according to a new study led by a Northeastern University research center.

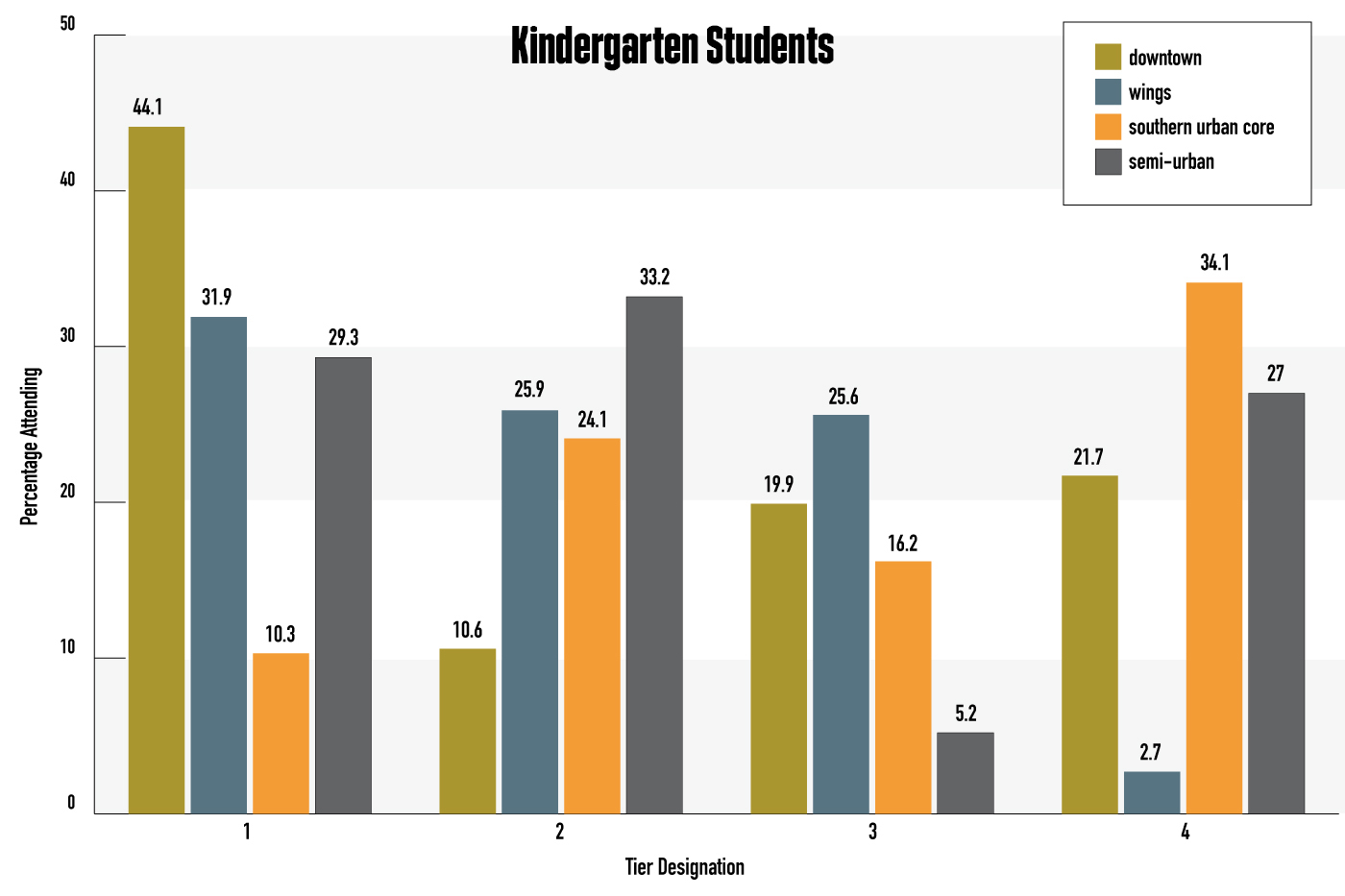

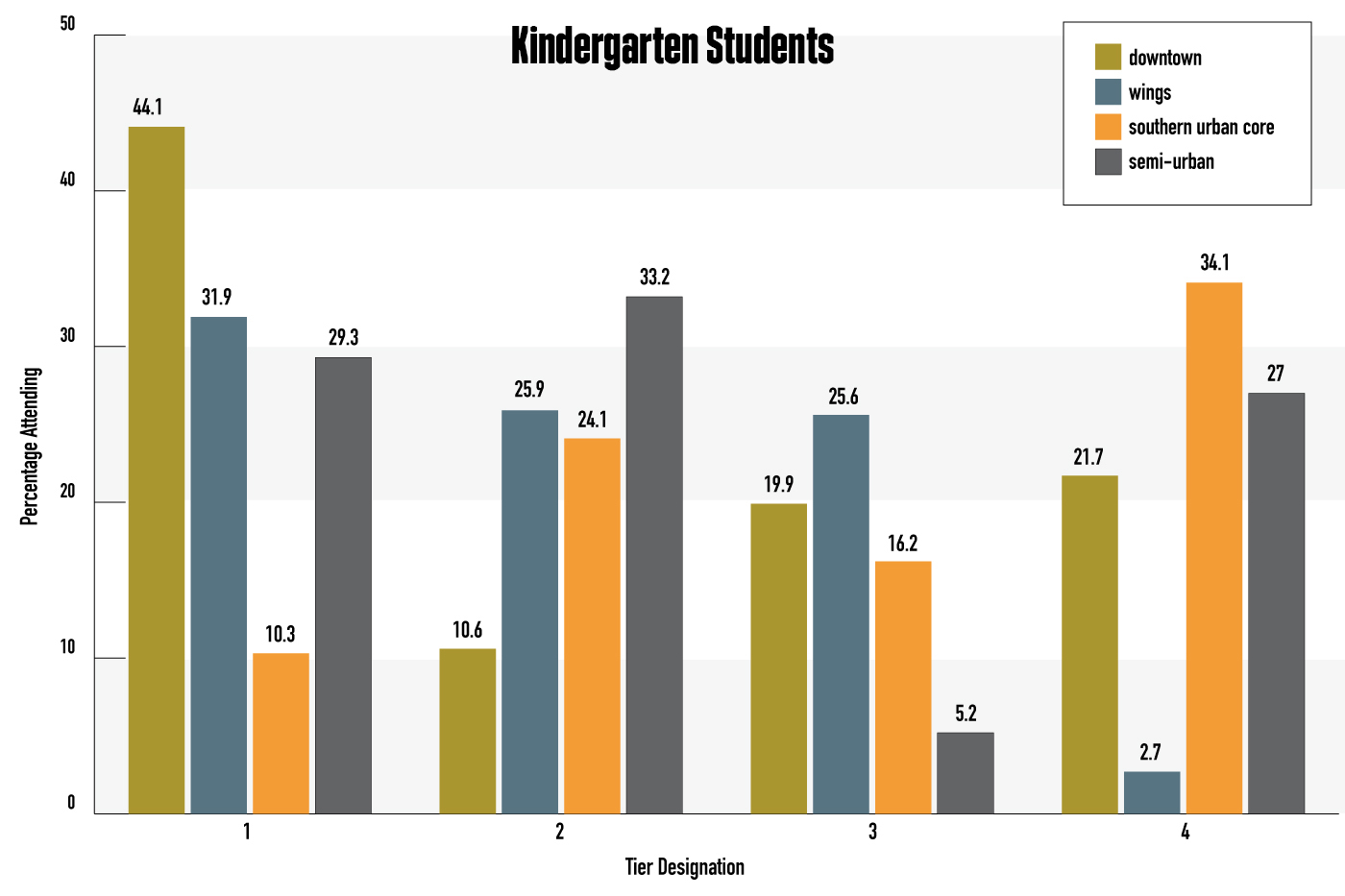

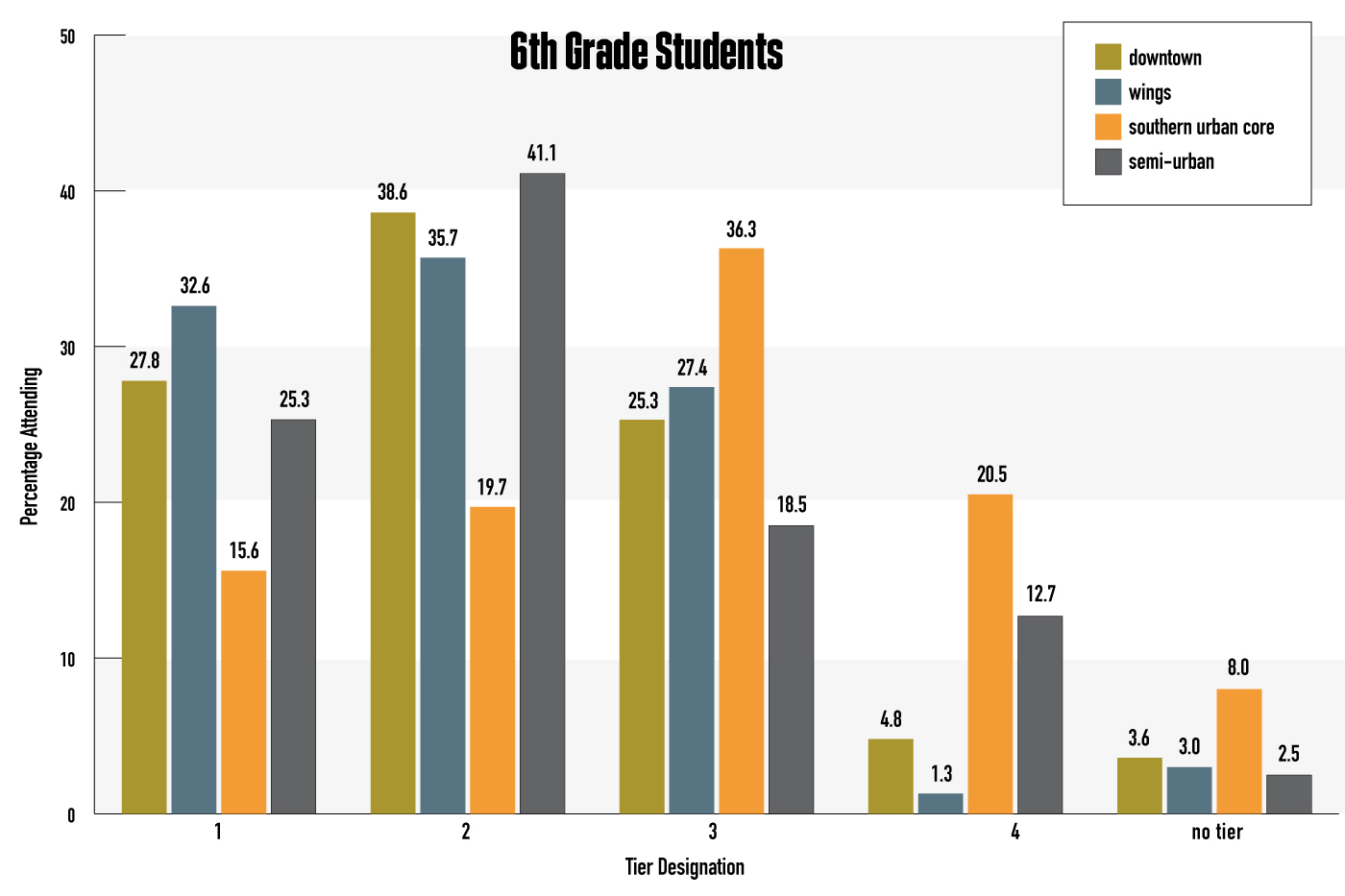

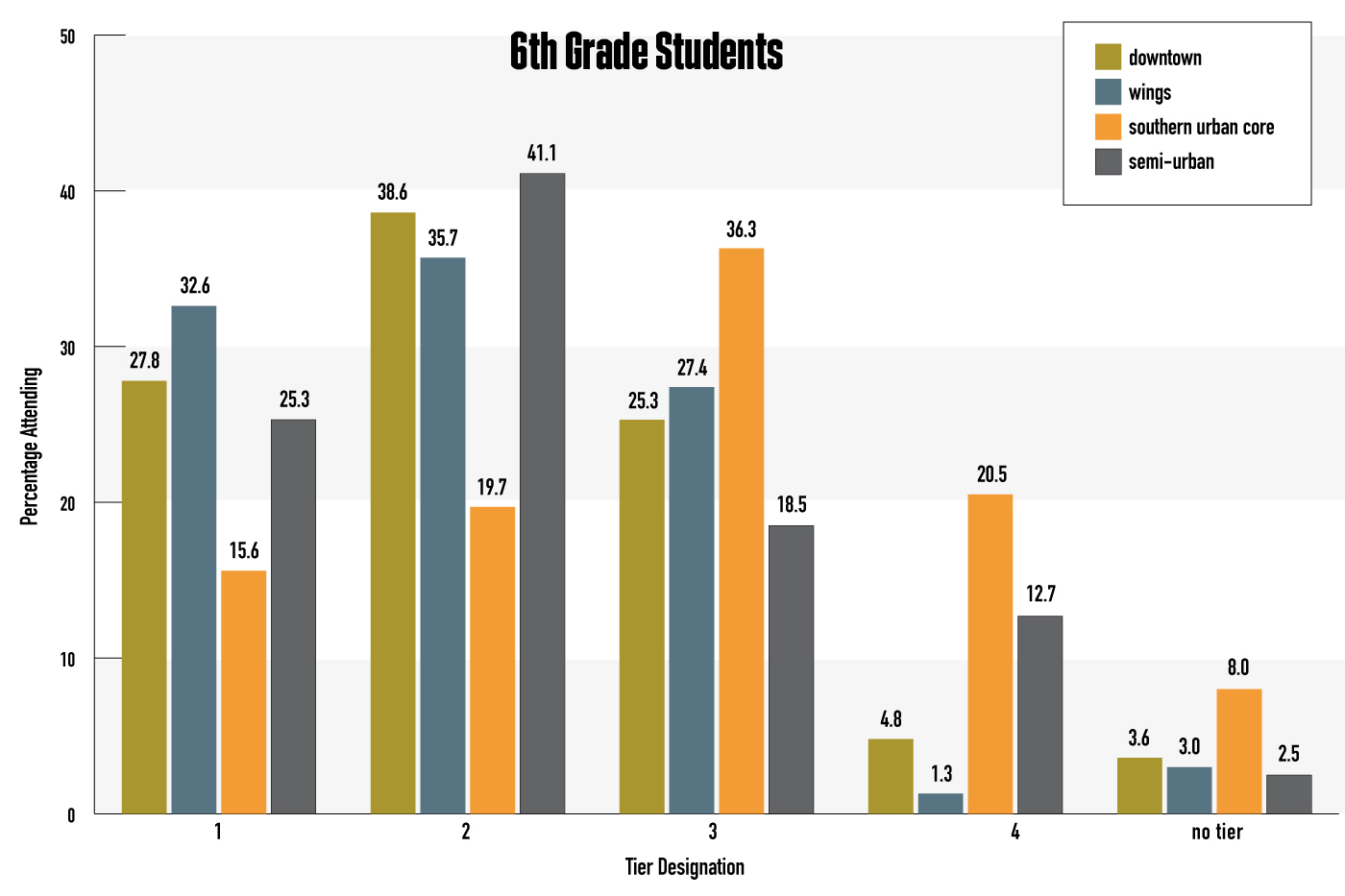

Four years ago, Boston began implementing a school assignment system that uses an algorithm to produce personalized school choices for families, with the goal of increasing students' access to high-quality schools while reducing the distance they have to travel to get to school Schools were ranked into one of four tiers based on their most recent MCAS scores and historical trajectory, with Tier 1 being the highest.

The researchers concluded that the new assignment system failed to address the city's long-standing geographic, racial, and socioeconomic disparities, noting that it in some ways further reduced geographic and racial integration across the region.

The study focused on evaluating the effectiveness of the system over three years for kindergarten and sixth grade. Boston Public Schools began implementing its new homework system for kindergarten and sixth grade during the 2014-15 academic year, and it has since been gradually rolled out to other grades.

One of the researchers' main findings is that geography largely determines access to quality schools. “If you don't have quality across the city, you can't provide equal access to quality,” he said Daniel T. O'Brienone associate professor in Northeastern's School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs and School of Criminology and Criminal Justice. O'Brien, lead author of the report, is co-directing it Northeastern Boston Area Research Initiativewho conducted the evaluation.

Researchers cited a lack of top-ranking schools near predominantly minority neighborhoods on the city's south side, including South Boston, Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan. Therefore, these students had fewer top schools to choose from, had more competition for places at those schools, were less likely to attend them, and had to travel longer distances to attend them.

If you don't have quality across the city, you can't provide equal access to quality.

Daniel T. O'Brien, Co-Director of the Boston Area Research Initiative;

The researchers found that pre-existing disparities in the number of students living in different parts of the city led to more competition for places for black and Latino students, compared to white and Asian students. As a result, they highlighted the need for a system that determines access to quality based on competition for places rather than the number of school choices.

“Using the problem of having fewer first-tier places available in these communities, there are more students vying for those places,” he said. Nancy E. Hill, co-author of the report and Charles Bigelow Professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. “Because more children applied for fewer places in those communities, fewer children in those communities got their first choice. And successively, more of these students were placed in Tier 3 and Tier 4 schools or were administratively assigned.”

The researchers presented their report to the Boston School Board on Monday night.

Other top finds:

- The new system achieved one of its main goals: for students to travel shorter distances and shorter periods of time to and from school. Specifically, the top 25% of commutes among kindergarten students were reduced by half a mile and two and a half minutes each time.

- The system has failed to create “neighborhood schools” — in which neighborhoods concentrate their students in fewer, more local schools.

“The homeschooling system was designed in such a way that it failed to address many existing inequities and, in some cases, exacerbated them,” O'Brien said..

The previous system of schoolwork divided the city into three zones. Under the new system—the algorithm for which was created by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology—each family had the opportunity to choose from at least six top-tier schools, including the two closest top-tier schools.

The researchers analyzed administrative records, including school choice options in both the current and previous assignment systems, as well as enrollment data for both systems. They also looked at data from the public school lottery process, including the choices submitted by families and the steps by which they were assigned to schools.

Another finding, Hill said, was a “surprise and avoidable” error in how the sixth-grade system was implemented. Families had to access the two closest Tier 1 schools for sixth-graders, but the algorithm was set to determine school quality based on the closest Tier 1 kindergarten schools. As a result, schools that do not offer sixth form were eliminated and pathway schools were added.

“Abolition of schools without a sixth form, in many cases, meant that there were no first-grade schools left,” Hill added. “The result was that many communities did not have access to primary schools by the sixth form.”

Increasing the number of good schools in the region is the most direct way to improve equity and access to high-quality education for all, the researchers said.

“We can't ignore the fact that black and Latino kids, who are already disadvantaged in other ways, face more competition to get into top-tier schools,” Hill said. “The deck is already stacked against them in this society, and this policy has made it harder for them to get the educational foundation they need to succeed.”