Voters in Iowa and New Hampshire traditionally help determine the Democratic and Republican presidential nominees, but reforms to the election calendar are long overdue, one expert says. Another says change is hard.

Iowa's caucus on Monday and the New Hampshire primary a week later are quickly losing their relevance because of changing demographics and historically poor forecasting results, two Northeast experts say.

By attending the two primary events, voters in Iowa and New Hampshire have traditionally helped provide an early picture of which Democratic and Republican candidates are performing well. But reforms to the electoral calendar are long overdue, an expert says. Another says change is hard.

“People who care about democracy have been wanting to overhaul this system for decades,” he says Jeremy R. Paul, professor of law and former dean of the Northeastern University School of Law. “Because the system as it is now has been terrible about the fact that two small, overwhelmingly white states play a huge role in choosing the presidential nominees.”

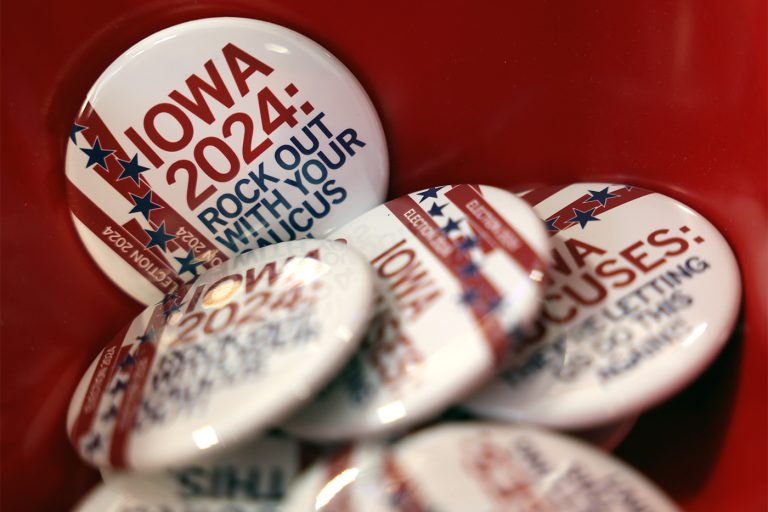

The Iowa Caucus is a statewide event where registered voters gather at caucuses to discuss and vote on their preferred candidates. Caucuses differ from primaries in that voters do not officially vote — instead, their votes are cast and counted privately by party representatives.

Historically, neither the Iowa caucuses nor the New Hampshire primaries have been very predictive. You'd have to go back to George W. Bush in 2000 to find the last non-incumbent Republican candidate to win the presidency after winning Iowa.

Since the modern primary system began in the early 1970s, there have been eight presidential candidates who won in Iowa but ultimately failed to secure their party's nomination, according to alphabet. There were 16 instances where the winner in Iowa failed to become president.

In 2020, then-candidate Joe Biden placed fourth in Iowa and fifth in New Hampshire before going on to secure his party's nomination.

In recent years, the nominating contests in Iowa and New Hampshire have been a source of seemingly endless surprise. for both parties — so much so that Democrats revamped their own calendar, putting South Carolina ahead of the two red states, in a move that upset many there.

“In the long run, how long the current system will last is anyone's guess,” says Paul.

With Donald Trump leading the Republican racethe Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primaries matter more to the second- and third-place candidates, who need strong finishes there to continue to support themselves, Paul says.

What alternatives to the current caucus and primary calendar (and process) have been proposed? An alternative that the National Association of Secretaries of State has advocated is a regional or rotating primary system, where groups of states would vote together to project a more demographically representative picture of presidential support.

“It would be much better if we divided the country into regions, in whatever way makes sense, then we would alternate the order in each circle,” says Paul.

Kostas Panagopoulos, head of Northeastern's political science department, says one of the benefits of the current sequential primary system is that it “lets learning happen.” States voting after January receive information from early voting that voters can use to evaluate the performance of specific candidates.

But Panagopoulos, who has conducted research on the disadvantages of congressional staff, admits that leading the presidential election process with states like Iowa and New Hampshire can skew expectations.

“I think there are good reasons to be concerned about the demographic makeup of early voting states, in part because their populations may not reflect the broader populations of the country,” he says.

Far from perfect, Panagopoulos says the challenge of reforming the system is one of coordination.

“Part of the complication is that these decisions take place at the state level and it's very difficult for national parties to coordinate on a national calendar when member states may or may not be willing to agree to certain changes or reforms,” he says.

“There's some evidence that the influence of places like Iowa and New Hampshire could be waning, and that may be because of the nature of their populations,” Panagopoulos adds, “but there's stronger evidence that what happens in the first primary in South [South Carolina] … may be more predictive.”

Ultimately, there are many different ways to organize the country's presidential nomination system, experts say. but incentives must be aligned across the board.

“States like New Hampshire have a huge incentive to keep things the way they are, and there's little incentive from anyone else to make a change,” Paul says.