This week, we learned that the US Supreme Court is poised to be overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 case that guaranteed an individual's right to obtain an abortion in the United States. If that happens, 23 states could enact abortion bans, according to NBC News Referencesleaving people in those states with few options.

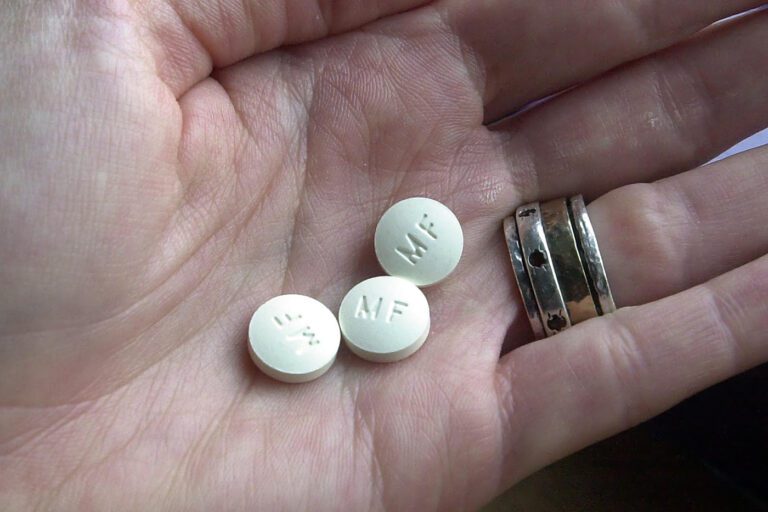

One option that is sure to create friction in the courts in the coming months is the abortion pill. Marketed as mifeprex and misoprostol, the drugs — when are taken in combination—is safe and effective (according at the Kaiser Family Foundation, has a 99.6% success rate) way to end a pregnancy in 10 weeks or less.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, this type of abortion accounted for for 54% of all terminations in eight weeks or earlier in 2020, with its popularity growing every year. And in December of last year, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) made the pills more affordable from removing the requirement to be prescribed in person. This opened up the possibility for patients to order the drug by mail or get a prescription through a telemedicine visit.

“There are strong arguments to say that a state cannot [ban abortion pills]but nothing is guaranteed right now,” he says Wendy E. Parmet,

Distinguished Matthews University

Professor of Law and Professor of Public Affairs

of Politics and Civil Affairs. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

If Roe is reversed, however, this upward trend in usage could be halted. If states are given the power to ban abortions, could that extend to banning a Federally approved drug or preventing it from entering the state?

The answer is complicated, he says Wendy Parmett, Matthews Distinguished Professor of Law at Northeastern University. He says the question highlights the ongoing tension between state jurisdiction and federal oversight in the American legal system, and it's hard to predict who will win in future battles over access to abortion pills.

On the one hand, Parmet says, federal courts defer to the states when it comes to issues like health and safety and the regulation of medicine, and that they could do the same when it comes to abortion pills. “At times, though not consistently, the courts will say we give it respect,” he says.

At the same time, there is the issue of federal preemption.

“Where the federal government has authority, it can preempt or override state actions,” Parmet says. “He does this all the time. Surely it can; For example, the FDA can make a drug illegal, and a state can't make it legal.”

There are also cases of what Parmet calls a “truce” between the two sides, as in the case of cannabis. Cannabis is illegal under the federal Controlled Substances Act. But states create their own laws for the sale and use of cannabis without federal consequences.

It's unclear whose jurisdiction the abortion pills would fall under—federal or state—because, Parmet says, in the legal system a case like this “goes both ways.” Some legal scholars have argued that federal precedent will apply, Parmet says, and that, if Roe overturned, states should not be allowed to create their own laws the way they did with cannabis.

However, Parmet is not sure that will happen under the current legal system, citing recent decisions such as the Supreme Court decision against the Occupational Safety and Health Administration's federal vaccination mandate and a federal judge decision to overturn the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) mandate for a mask.

“I can imagine a federal court saying abortion is an important issue and the federal government can't preempt state power unless it's absolutely clear,” he says. “I think it would be wrong and worrying, but I can imagine it.”

Meanwhile, while states may not be able to outlaw the pills, they are working to make them less accessible. In response to the FDA's loosening of drug regulations, state lawmakers have already proposed more than 100 restrictions on abortion pills in 22 states, according to the New York Times. Some states require the pill to be taken in a doctor's presence, and some prohibit prescriptions from being taken by mail or through a telehealth appointment. These restrictions are legal, Parmet says, likely because they don't conflict with FDA regulations.

Tougher measures, such as criminalizing mail-order abortion pills, may be difficult to implement. States aren't likely to track what's shipped via FedEx or USPS, Parmet says. But when it comes to making it illegal to possess or prescribe abortion drugs, that's up in the air.

“There are strong arguments to say that a state can't do it, but nothing is guaranteed right now,” he says.

Issues like residency raise even more questions. Can a state criminalize travel to another state to obtain an abortion or abortion medication? Can an out-of-state resident, or a group of pro-choice advocates, be prosecuted for helping an in-state resident terminate a pregnancy? Can someone be prosecuted for transporting pills? “We don't know how the courts will rule on these issues,” says Parmet.

The only certainty, it seems, is that it is impossible to predict what meta-Roe America is similar.

“When the court issues its decision [Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization]this will not be the end of the story,” says Parmet.