Forests in the eastern United States have undergone a radical transformation since the era before European colonization, according to a new study.

By comparing the modern composition of forests in nine states, in an area from Maine to Pennsylvania, with geographic survey records describing these forests in pre-colonial times, researchers from the Smithsonian Institution found that while the species and diversity of of trees are mostly the same. Their distribution and numbers are very different from 400 years ago.

“The modern forest is complexly different from the pre-colonial situation,” the scientists write in a paper was published on Wednesday, September 4 in the journal PLOS One.

Most of this change is the result of intensive logging and agricultural clearing that began around 1650 and continued for the next two centuries. These cleared areas were then naturally reforested as the trees returned.

In addition, the researchers found that modern forests are more homogeneous and their composition is not as affected by local environmental factors such as rainfall, temperature and altitude. Despite the geographical distance, the forest composition between “any two cities, on average, are slightly more similar in modern times than it was in the colonial period,” according to the study.

The graph below shows how the composition of forests has changed over the past four centuries. Beech, oak, hemlock, and spruce are much less abundant today, while fir, cherry, and maple have increased since pre-colonial times. American chestnuts almost completely disappeared in the early 20th century due to an invasive fungus that persists today.

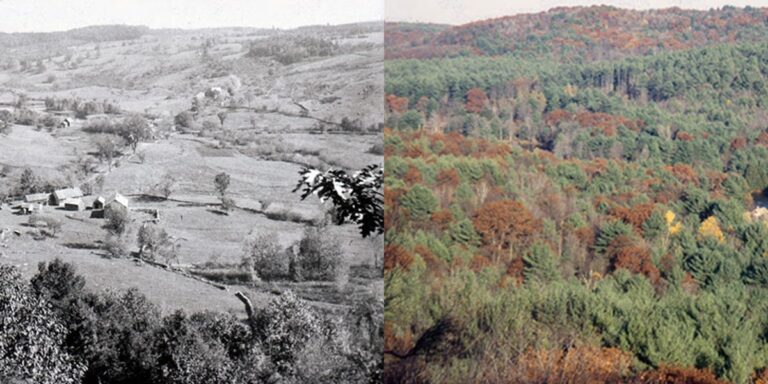

You can see how different the forests are:

Across the region, beeches—large deciduous trees distinguished by smooth, gray bark—showed the greatest decline in abundance, falling from an average of 22% in pre-colonial times to 7% today. The most notable changes are in Vermont, western Massachusetts, and northern Pennsylvania. Beech abundance remained the same in New York's Adirondack Mountains, the study found.

Oaks suffered a significant decline in abundance, from 18% in pre-colonial times to 11% in modern forests. Oak decline was most severe in central Massachusetts and southwestern Pennsylvania.

Hemlock trees have declined from 11% in pre-colonial times to 7% in modern times.

Maples experienced the greatest absolute change in relative abundance and now dominate the northeastern US, increasing across the region from an average of 11% in the past to 31% today.

A view of the Swift River Valley in Central Massachusetts, photographed in 1890, showing extensive forest clearing for agriculture.

The same view photographed today shows the recovery of forests in many areas of the northeastern US