In the coming decades, increases in winter temperatures associated with global warming could greatly expand the range of the southern pine beetle—one of the world's most aggressive tree-killing insects—across much of the northern United States and southern Canada. , says a new study. The beetle's range is sharply limited by annual low temperature extremes, but those lows are rising much faster than average temperatures — a trend that will likely drive the beetle's spread, the authors say. The study was published today in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The study points to “huge vulnerability in a huge ecosystem,” said lead author Corey Lesk, a researcher at Columbia University's Center for Climate Systems Research and an incoming graduate student in the university's Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences. “We could see loss of biodiversity and iconic regional forests. There will be damage to the tourism and forestry industries in already troubled rural areas.” Co-author Radley Horton, a researcher at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said contaminated forests could also dry out and burn, endangering property and releasing large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

Until recently, southern pine beetles ranged from Central America to the southeastern United States, but in the past decade or so they have begun to appear in parts of the Northeast and New England. Significant outbreaks began in New Jersey in 2001. The beetles were first found in Long Island, New York in 2014, and in Connecticut in 2015.

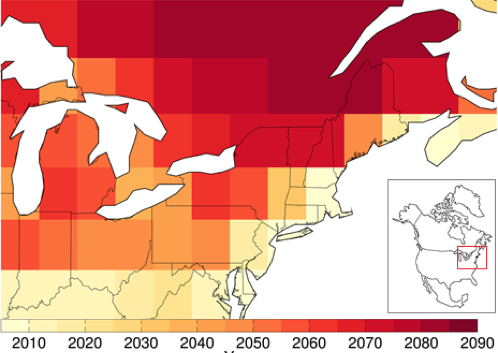

Lesk and Horton predict that by 2020, the beetles will be established along the Atlantic coast as far away as Nova Scotia. They say that by 2050, 78 percent of the 48,000 square miles now occupied by pine forests from southern Maine to eastern Ohio will have climates newly suitable for the beetles. By 2060, they expect the beetle to establish further from southern New England through Wisconsin, and by 2080, climates suitable for the beetle will reach 71 percent of red pines and 48 percent of pines, spanning over 270,000 square miles in the northeastern United States and southern Canada.

The research is part of a larger body of work in which Lesk and Horton aim to identify the risks to species and ecosystems associated with changes in temperature extremes. Many species are sensitive to highs and lows, which are expected to see large fluctuations in frequency and intensity as the climate warms. The researchers chose to focus on the southern pine beetle because it has a huge impact on forest ecosystems, and the influence of cold boundaries on its range has been well documented since the early 20th century.u century. Pine beetle infestations in the southeastern United States cost about $100 million annually in timber losses from 1990 to 2004 alone, according to the US Forest Service.

Previous such analyzes have mostly looked at average July temperatures or average January temperatures, said Matthew Ayres, a professor of ecological science at Dartmouth College who has studied the beetles. That might seem reasonable, he said, but “that variable, the coldest night of winter, is very important for all kinds of things.” The coldest winter night has warmed by about 6 or 7 degrees Fahrenheit over the past 50 years at weather stations in many parts of the United States, compared to just 1 degree Fahrenheit for average annual temperatures. Horton and Lesk project additional increases in annual minimum air temperatures of 6.3 to 13.5 degrees Fahrenheit in the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada by 2050 to 2070.

The researchers looked closely at New Jersey, where the spread of the beetles occurred amid a warming trend in cold extremes. The temperature of the pine bark on which the beetles feed, which is warmer than the air, is apparently the critical factor. The northernmost observations were largely associated with latitudes where winter crustal temperatures reached at least 14 degrees Fahrenheit. Since 1980, winter minimum crustal temperatures of 14 degrees have migrated northward in New Jersey by about 40 miles per decade. The northernmost sightings of the beetles have drifted north about 53 miles per decade since 2002.

To account for uncertainties in their predictions, Lesk and Horton integrated 27 different global climate models and two greenhouse gas emissions models. They also consider the possibility that the beetles could not travel through hardwood forests with sparse pine trees in the northern United States. However, beetles have already accomplished this feat in many areas. Overall, the researchers found that the uncertainties resulted in a 43-year range between the earliest and latest year a climate suitable for the beetles would be expected to occur on average across the study area.

The paper did not consider some uncertainties, such as the possibility that cold extremes could change more dramatically than climate models suggest if atmospheric circulation patterns or snow cover shift in unpredictable ways. There are also questions about how the beetles might respond to droughts or heat waves. how vulnerable will northern pine species be to beetle attacks? and how rising temperatures may affect the beetles' natural predators, such as the spotted beetle.

Land managers further south have used adaptive strategies with limited success, primarily thinning forests where tree density is high or cutting infected trees. The question is whether these strategies will work in the north.

The other authors of the study are Ethan Coffel of Columbia University. Anthony D'Amato of the University of Vermont and Kevin Dodds of the USDA Forest Service.